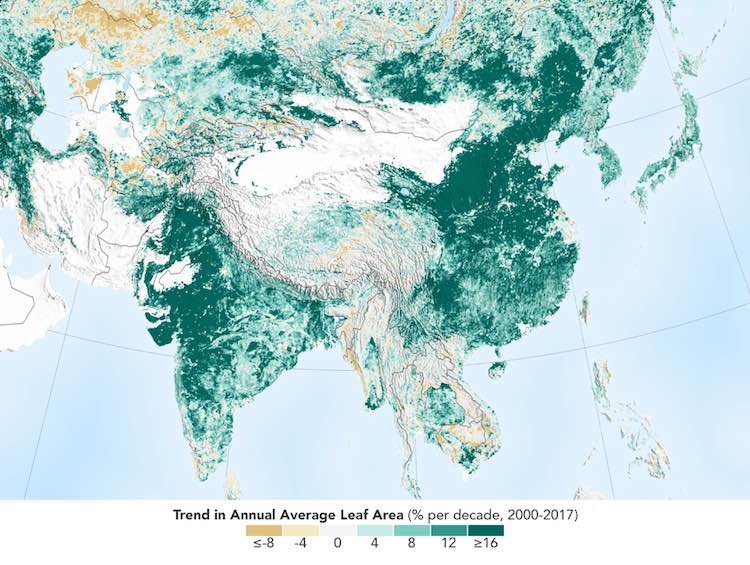

The planet is actually a greener place than it had been 20 decades back, along with the information from NASA satellites has shown a counterintuitive resource for a lot of the new foliage: China and India.

This astonishing new study proves that both emerging nations with the world’s most significant populations are contributing to the progress in greening on Earth.

The greening occurrence was initially detected by investigators using satellite information in the mid-1990s; however, they didn’t understand whether human action has been among its main, direct triggers.

This fresh insight was made possible with a practically 20-year-long data recording in the NASA instrument orbiting the Earth on two satellites. It is known as the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer, or MODIS, and its own high performance data provides very precise advice, assisting researchers work out specifics of what is happening with Earth’s volcano down to the amount of 500 meters, roughly 1,600 ft, on the floor.

Taken all together, the greening of the world during the past two decades signifies an increase in leaf area on trees and plants equal to the area covered by most of the Amazon rainforests. There are more than two thousand square miles of green leaf area each year, in comparison with early 2000s — that amounts to a 5 percent growth.

Lead author of the study, Chi Chen of the Department of Earth and Environment at Boston University said: “China and India account for one-third of the greening, but contain only 9% of the planet’s land area covered in vegetation – a surprising finding, considering the general notion of land degradation in populous countries from overexploitation.”

An edge of this MODIS satellite sensor is that the intensive coverage it offers, both in distance and time: MODIS has recorded as many as four pictures of each location on Earth, daily for the previous twenty decades.

“This long-term data lets us dig deeper,” said Rama Nemani, a research scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center and a co-author of the new work. “When the greening of the Earth was first observed, we thought it was due to a warmer, wetter climate and fertilization from the added carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, leading to more leaf growth in northern forests, for instance. Now, with the MODIS data that lets us understand the phenomenon at really small scales, we see that humans are also contributing.”

China’s outsized contribution to the worldwide greening trend comes from substantial part (42 percent ) from apps to preserve and expand woods. Another 32 percent there — and 82 percent of those greening found in India — stems from intensive farming of food plants.

The land area used to grow plants — over 770,000 square kilometers — is similar in China and India and it hasn’t changed considerably since the early 2000s; nonetheless these areas have significantly increased both their yearly total green leaf area and their food production. This was accomplished through multiple cropping clinics, in which a field is replanted to create another crop many times per year. Generation of grains, fruits, vegetables, and much more have increased by roughly 35-40percent since 2000 to nourish their large populations.

The way the greening trend can vary in the future is dependent upon numerous variables, both on an international scale and the regional individual level. By way of instance, greater food production in India is eased by groundwater irrigation.

“But, now that we know direct human influence is a key driver of the greening Earth, we need to factor this into our climate models,” Nemani said. “This will help scientists make better predictions about the behavior of different Earth systems, which will help countries make better decisions about how and when to take action.”

The investigators point out that the benefit of greenness seen around the planet, which will be dominated by India and China, doesn’t offset the harm from loss of plant in tropical areas, including Brazil and Indonesia. The implications of sustainability and biodiversity in these ecosystems stay, but complete, Nemani sees a positive message from the new findings.

“Once people realize there’s a problem, they tend to fix it,” he said. “In the 70s and 80s in India and China, the situation around vegetation loss wasn’t good; in the 90s, people realized it; and today things have improved. Humans are incredibly resilient. That’s what we see in the satellite data.”

This research is available online in the journal Nature Sustainability.

[…] 1,400-year-old Ginkgo Biloba tree in China attracts thousands of people every year to travel from all over the country and admire its […]